last edit: March 2022

We are interested in the different ways animal morphology and natural history becomes adapted to their biotic and abiotic environment. Some traits are extremely labile within species even across very restricted spatial scales (such as a group of islands) and temporal scales. Significant morphological changes can sometimes be detected over the course of a century or less, and presumably, they are evolutionary and adaptive.

We study natural history, life history, physiology and morphological variation within and between species at different spatial and temporal scales, and then compare the patterns of variation shown in whole clades or regions, to search for common evolutionary mechanisms that drive them. We mainly study reptiles, and often land vertebrates as a whole, both as models for biodiversity in general and because, well, they are fascinating in their own right!!

Our interests thus lay at an intersection of Evolutionary Biology, Biogeography, Macroecology and Zoology (mainly Herpetology, also Mammalogy and Ornithology, but we had and have projects on fish, frogs, and even, though we wil not always admit it, on arthropods)

We use four main approaches to study the phenomena we are interested in: Macroecological, Museum specimen based, lab based and field-based. We use published data, data we generate in the field, molecular data we obtain from specimens, and natural history, behavioural observations, life history data, and physiological data obtained in the field and in the lab

Macroecology

The advantage of macroecology is that phenomena are studied at very large spatial, temporal and phylogenetic scales, enabling generalizations to be valid. A macroecological approach also allows us not to leave the air-conditioned lab during the Israeli summer. Or macroecological work mainly focuses on the diversity, life history and reproduction, ecology and island biogeography of reptiles. This often neglected group of terrestrial vertebrates is species rich (it is the largest tetrapod class) and highly variable. Reptiles are beautiful and fascinating animals as everyone who has studied them closely can attest. We are trying to erect a global dataset of the geographic ranges, ecological, morphological and natural history traits, as well as the phylogenetic relationships of reptiles that will allow us to seek patterns and test hypotheses regarding their evolution. We now also focus much attention on conservation and conservation planning, species assessments (Shai is the redlisting authority for the skink specialist group). This is done in collaboration with many scientists, especially Uri Roll, Reid Tingley, and Dave Chapple

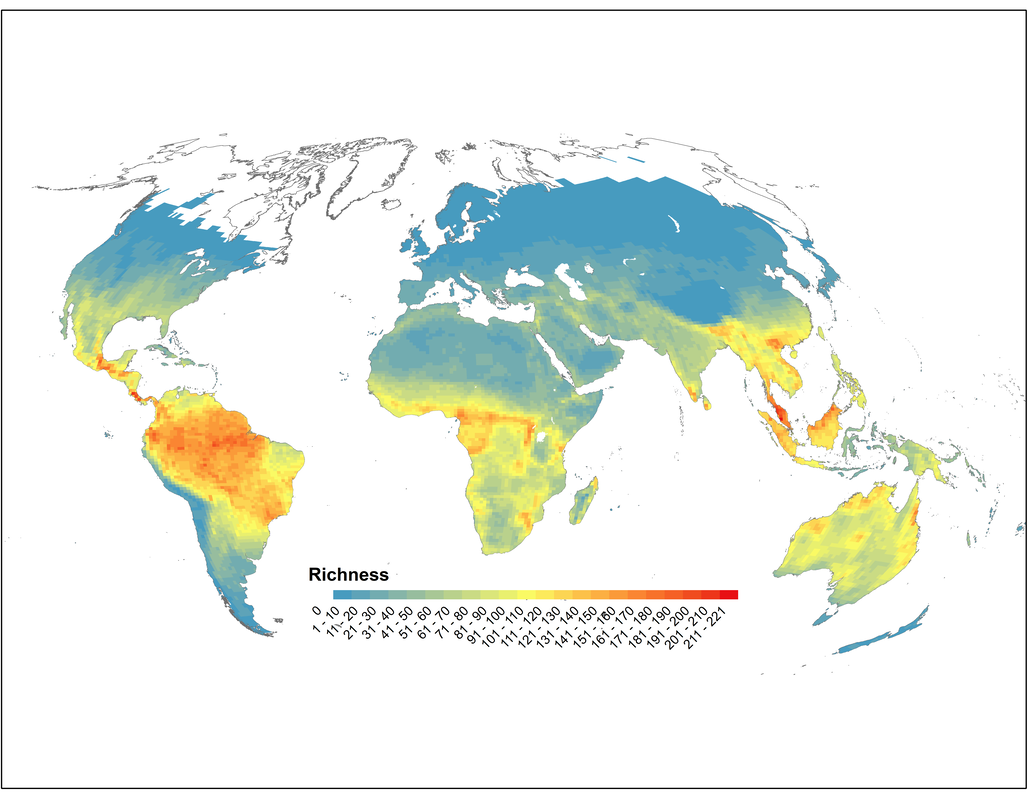

With the help David Orme, www.geog.ox.ac.uk/staff/rgrenyer.htmlRich Grenyer, Aaron Bauer, and the members of our Global Assessment of Reptile Distributions working-group (GARD), we examine factors that affect the distribution and evolution of lizards. We are trying mapping reptile distribution globally (a work that many of the lab's best alumni, especially Anat in charge of snakes, Yuval of tortoises, crocs and the tuatara, and Maria taking care of small-island reptiles led successfuly). Our wonderful collaborator, Uri Roll is making the calls that require a responsible-adult. We study diversity patterns (e.g., Tal Raz's work), as well as other macroecological phenomena (relationships of features such as body size, range size, range position, macropgysiology, taxonomic trends, and trait geography etc.). Enav studied the distribution of Palearctic lizards as well as their functional diversity, comparing them to the nested subset of Israeli lizards to examine the effect of scale on these metrics, as part of her PhD project (co-supervised by Yoni Belmaker). Nowadays Chen studies the diversity of burrowing reptiles, and Anuj studies the distribution of reptile activity times, whereas Anna studies the distribution of life history traits.

With Gopal Murali, a joint postdoc at ours and Uri Roll's the lab, we study diversification rates of squamates, and of vertebrates in general. We aim to simultaneously test multiple hypotheses related to causes of variation in diversification rates - see here for details. Gabriel Caetano, meanwhile, looks at new ways to classify and assess extintion risk and threat status of reptiles, both using supervised machine learning methods to assign species with IUCN-like evaluations, and unsupervised methods to acheive a more nuanced view that more readily incorporates future threats, such as those of land-use change and climate change (which Gopal also studies intensively).

We are now working on producing better reptile maps, better assessments, and better trait data, to ask multiple questions regarding trait evolution and conservation status, among other things (and there is always room for the prospective student).

"No statistical procedure can substitute for serious thinking about alternative evolutionary scenarios and their credibility" Westoby, Leishman and Lord, 1995. On misinterpreting 'phylogenetic correction. Journal of Ecology 83: 531-534.

Biodiversity, Phylogeny & Taxonomy of reptiles

We aim to help resolve the phylogeny, taxonomy and distribution of reptiles worldwide, and especially in Israel Thus, for example, we established the number, identity, phylogeography and distribution of Israeli "thin" racers of the Platyceps rhodorachis/saharicus/tesselata/ladacensis complex (Guy's MSc. project, which was done in collaboration with Roi Dor, there is only one: P. saharicus), and Simon's project on Micrelaps (again there is only one in Israel). Some of the lab's postdocs and former postdocs are actively working on deciphering the diversity of Israeli reptiles using molecular and morphological taxonomy methods. Thus for example Karin and Alex are working on Hemidactylus, Tali and Marco are working on Chalcides sepsoides (and the Amaonian Plica), Tali also works on Myriopholis, and Marco studies the taxonomy of multiple reptile taxa including Elaphe and Pseudopus (with Daniel Jablonski), Tropiocolotes geckos, Telescopus snakes and other taxa. We are very excited to have Roberta Graboski Mendes joining the team to work (with Aaron Bauer) on a broad phylogenetic survey of all Israeli reptiles both within the country and by comparing them to populations ranging from the Sahara and the Sahel to southern Europe and the deserts of Central Asia and the Arabian Peninsula.

The region as a whole, from Algeria, Chad and Lybia in the west, Sudan and S. Sudan and even further in the south, Lebanon and Syria in the north, and Jordan and Iraq in the east, as well as Israel itself, has a rich reptilian fauna that went mostly unstudied in terms of taxonomy and molecular phylogenetics. We hope to take steps to amend this (and are always happy to collaborate, and train new students in relevant methods).

Other taxa & projects

Quite often we study animals that are (horor, shock) not tetrapods. Thus Miachaela studies the ecology and phylogenetics of larval fishes, through their ontogenetic development (with Roi Holzman), Guy studies the taxonomy and phylogeny of Israeli leaf hoppers (Insecta: Hemiptera; with Christopher Dietrich), and the vertebrate and invertebrate communities of Mediterranean temporary pools are studied by Yan and Shoham (with Frida Ben-Ami) - looking at the factors contributing to their biodiversity and whether they promote biodiversity not only in winter when the pools are full but also in summer when they are dry. Lastly, Adva studies an extinct tetrapod, a mammal, the water vole - and assesses its Pleistocene and Holocene populations (with Nimrod Marom) as well as the feasibility of its reintroductions. We aim to expand our probing into the biodiversity of Israel's Pleistocene and Holocene mammal fauna, collaborating with Nimrod, Meirav Meiri, and Guy Bar-Oz.

Museology

We examine and measure museum specimens of birds, mammals, amphibians and reptiles in museums across the world in order to study both current patterns of diversity and body size evolution – and temporal changes in both these axes that may have important conservation implications as well as teach us important lessons regarding the tempo and mode of evolution. Thus, for example, we study, body size changes in recent time in relation to climate change and other anthropogenic influences with Inon Scharf - and as part of the PhD project of Shahar.

We likewise acquired a large dataset of carnivore skull and teeth measurements (currently > 24600 measured specimens belonging to 248 – nearly all carnivore species) and a slightly smaller dataset (~1000 specimens) of treeshrew measurements. We use these data mainly to examine the forces that affect body size evolution (often in collaboration with Tamar Dayan and Dan Simberloff), especially in relation to insularity, climate, resources, and community composition.

And of course we use museum specimens from the collections of the Steinhardt Museum of Natural History and other institutions, for mapping species distributions (e.g., with Uri Roll and Enav Vidan), studying taxonomy and phylogeny (see above) as well as morphological evolution.

“...What is needed in a collection of natural history is, that it should be made as accessible and as useful as possible on the one hand to the general public, and on the other to scientific workers... What the public want is easy and unhindered access to such a collection as they can understand and appreciate ; and what the men of science want is similar access to the materials of science. To this end the vast mass of objects of natural history should be divided into two parts, -one open to the public, the other to men of science, every day, and all day long." Tomas Henry Huxley 1877. On the study of biology. American Naturalist, 11: 210-221.

Field studies

We don’t participate in nearly as many field studies as we would like (but we’re working on remedying this). We are trying to survey the Israeli Herpetofauna and soricofauna (now here’s a term we assume no one has ever used before! shrew fauna) in the field. We also have a fascinating collaborative study (with Panayiotis Pafilis in the University of Athens) where we study the life history of the lizards Podarcis erhardii and Podarcis gaigeae, and the geckos Mediodactylus kotschyi and Hemidactylus turcicus, as well as other lizards and snakes, on various islands in the Aegean Sea, Greece. These small lizards (the lacertids similar to Israeli Phoenicolacerta laevis) often become larger on small islets, but sometimes grow smaller. Podarcis gaigeae get especially large on a speck of rock that different cartographers argue should be called either Mesa Diavates or Exo Diavates – a giant Diavates male can attain a mass of 20 grams, 3 times heavier than a mainland male. We do field work on Skyros and its adjacent islands, and especially, in the Cyclades Archipelago, and sometimes on other Greek islands trying to quantify morphological, life history, physiological endocrinological and behavioural differences between population inhabiting different islands (genetic differences were found to be minimal, but we are looking further into that as well, with Nikos Poulakakis). We also look hard for possible drivers for the observed differences, especially those related to arthropod abundance, vegetation structure, goat and sheep grazing, sea bird nesting and the usual suspects of island biogeography theory (area and isolation). We compare various traits and their variances between islands and to mainland populations. Rachel is studying these lizards in Greece - and the tree gecko (M. orientalis/ M. kotschyi, interestingly it is not a tree gecko in Greece, but is mostly saxicolous there) in Israel as well.

Simon's project looking at the natural history of little-known Israeli snakes and lizards: Eirenis decemlineata, Ophiomorus latastii, and Micrelaps muelleri) across the Mediterranean biome in Israel. Rachel is studying microhabitat and its effects on Israeli reptiles along a climatic gradient. We try to study basic natural history of Israeli reptiles - and their conservation need, in the field as much as we can.

Reptile physiology

Rachel studies the effect of micro and macrohabitats on gecko physiology (water loss, digestive efficiency, metabolic rates, temperature preference), managing more PIs than anyone else, being formally co-supervised by Dave Chapple, but collaborating with Panayiotis Pafilis, Eran Gefen, Eran Levin and potentially others I forgot. Shahar is taking a comparative approach, both macroecological and field and lab based, to study the effects that the diel cycle, thermal behaviour, season (brummating vs. active individuals), and geography, have on reptile metabolism, thermal traits, water loss rates, fatty acid utiization, and organ size (all in the lab of Eran Levin)

"It (ecological equilibrium) has the disadvantage of being untrue. The 'balance of nature' does not exist" C.S. Elton 1930 Animal ecology and evolution" P. 17

Richness of 11,525 species of reptiles (raw data, polygons and points, non-modelled ranges), September 2021